Technology decisions inside law firms are rarely made in a single room by a single group. They emerge through committees, informal conversations, urgent emails and well-intentioned exceptions.

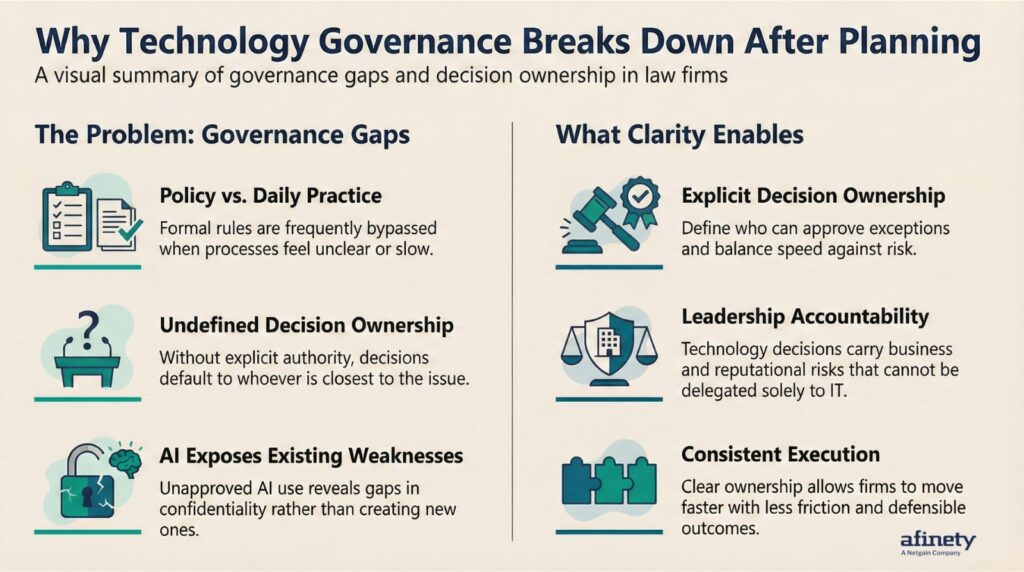

On paper, many firms have governance structures in place. In practice, it is often unclear who actually owns technology decisions once planning ends and execution begins.

That lack of clarity creates risk. Not because firms are careless, but because modern legal technology moves faster than traditional decision models were designed to handle.

Governance is not a policy document

Many law firms equate technology governance with written policies or standing committees. Those are necessary, but by themselves, they are not sufficient.

True governance shows up in day-to-day decisions. Who approves new tools? Who determines acceptable AI use? Who decides when security controls can be bypassed to keep work moving?

The American Bar Association Legal Technology Survey continues to show gaps between policy and practice. Firms often have formal rules in place, yet attorneys and staff still make technology decisions independently when processes feel unclear or slow. When pressure hits, governance that exists only on paper tends to fly out the window.

Decision ownership breaks down after planning

Technology planning cycles usually establish priorities and budgets. What they often fail to establish is ownership once the year is underway.

As new issues arise, firms struggle to answer basic questions:

- Who has the authority to approve exceptions?

- Who balances speed against risk?

- Who revisits priorities when conditions change?

Research from MIT Sloan’s Center for Information Systems Research on decision rights shows that organizations perform better when decision authority is explicit and understood before disruption occurs. Without that clarity, decisions default to whoever is closest to the problem.

In many firms, IT leaders see the risk early but lack clear authority to intervene. This leaves them responsible for outcomes but without control over the decisions that created them.

AI has exposed governance gaps

AI adoption has amplified existing governance weaknesses. Many firms attempted to delay AI decisions or restrict use entirely. In reality, attorneys began experimenting anyway, often outside approved systems.

As we’ve said before, banning AI does not stop usage. It simply moves it out of view, increasing risk rather than reducing it. When governance is unclear, firms face inconsistent answers to critical questions about confidentiality, acceptable use and client disclosure. AI did not create this problem. It revealed it.

Many firms start by clarifying ownership for just one decision category, often AI use or security exceptions, before attempting to formalize governance more broadly.

Committees are not decision engines

Technology committees are common in law firms and often well-intentioned. The issue is not their existence, but their design. Committees that meet infrequently or lack clear authority struggle to keep pace with modern technology demands. Urgent decisions get made outside the process. Long-term priorities get delayed.

CIO research on technology governance emphasizes that committees work best when they function as decision frameworks rather than discussion forums. Without defined decision rights and escalation paths, committees slow execution instead of enabling it.

In many firms, the most effective committees focus less on consensus building and more on decision escalation when tradeoffs need leadership input.

What effective governance looks like in practice

Firms with effective technology governance tend to share a few characteristics.

- Clear ownership for different types of decisions

- Defined criteria for risk-based tradeoffs

- Alignment between IT leadership and firm leadership

- Willingness to revisit decisions as conditions change

Governance is what allows firms to execute fewer initiatives more effectively rather than chasing every new request. The goal is not control for its own sake. It is consistency, defensibility and clarity.

Governance is a leadership issue

Technology governance is often framed as an IT responsibility. In reality, it is a leadership responsibility.

Client expectations, security requirements and professional obligations mean technology decisions now carry business and reputational risk. Those risks cannot be delegated entirely to IT teams.

Leadership engagement does not require weekly meetings or a heavy process. It does require agreement on decision rights and visible support when governance is tested.

Clarity enables progress

Law firms do not need more committees or longer policies. They need clarity. Clarity around who decides. Clarity around acceptable risk. Clarity around how priorities are enforced when pressure mounts.

When governance is clear, firms move faster with less friction. When it is not, even well-planned initiatives stall. Technology governance is not about slowing innovation. It is about making sure innovation happens intentionally, consistently and in a way the firm can stand behind.

If your firm is revisiting how technology decisions get made, governance is often the best place to start. Even a short conversation to clarify ownership can make every other initiative easier to execute.